Sound & Vision

It would be a full thirty years from film's beginnings, that they would finally themselves learn to speak, which is an astounding fact, considering that Mr Thomas Edison devoted himself to the idea that motion pictures were merely an extension of his talking machines in the 1880s. Edison, even would equip a number of his Kinetoscope peepshow machines with phonographs, and it was he that crowned them the 'Kinetophone' , unfortunately he was none to successful in matching sound to picture accurately enough to allow the image of the on screen person to appear to be actually speaking or singing.

And even so, films of the silent age, were rarely exhibited in silence. In 1897, the Lumiere brothers engaged a saxophone quartet to accompany the Cinematographe at their theater in Paris, The composer Saint-Saens was asked to score for the prestigious film production L'assassunat du Duc de Guise (The Assassination of the Duke de Guise) in 1908, and after this point, it became compulsory for all major feature length movies to have specially composed or compiled musical accompaniment. Music, therefore was a vital branch of the silent film business. It provided employment not only for the composers and musical publishers, but for these early session musicians who played at each peformance

The Luminary Lumieres

There would be other types of sounds associated with silent films beyond music, as writer Fredereick Talbot would indicate in his : Moving Pictures; How They Are Made and Worked :

'When a horse gallops, the sound of its feet striking the road is heard; the departure of a train is accompanied by a whistle and a puff as the engine gets under way; the breaking of waves upon a pebbly beach is reproduced by a roaring sound. Opinion appears to be divided as to the value of the practice.'

From the 1916 film Intolerance, Briel and Griffith unite

To include sound effects, cinema franchisers could equip themselves with specialized machines that produced a spectrum of noises, from bird song to cannon fire. The bugbear to these live accompaniments, was that they all depended so much on the availability and adroitness of the people making the noises - whether musical performers or basic machine operators, Frederick Talbot recalled an effects boy who 'enjoyed the chance to make a noise and applies himself a vigor of enthusiasm which over-stepped the bounds of common sense'.

The elaborate musical accompaniments devised by Joseph Carl Breil for the films of D.W. Griffith, or the musical suggestions supplied as a matter of course by the distributors in the 1920s, were one thing when the film was performed at picture palaces, but disparately when it arrived at some random backwoods fleapit with only a single, neglected piano.

Edison was well well on the case with his' Phonograph' years before anyone else.

From an early stage, it was evident that a truly satisfactory sound accompaniment must be recorded and then reproduced mechanically. The resources it seemed were at the ready. A decade, or more before the movies, Edison's phonograph and Berliner's disc-gramophone had facilitated mechanical sound. In the incubating stages of these had the disadvantage that even with sonorous trumpet-like horns for amplification, the volume of sound achieved was minimal ; but by the early Twenties, electrical recording and reproduction had assuaged this problem. The truest palaver would now be how to fit sound to image precisely.

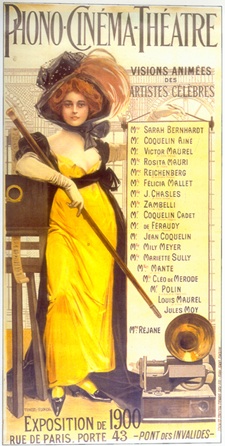

A poster from the 1900 Paris Exhibition

In the 1890s, a Frenchman, Auguste Baron, had patented several systems of synchronizing phonograph and projector. By the year 1900, there would be three competitive sound film systems, and each showcased at the Paris Exposition. The most impressive of the lot, was the Phono-Cinema-Theatre of Clement-Maurice Gratioulet and Henri Lioret (who had previously patented a cylinder reocrding device - the Lioretographe). First shown at the Exposition on June 8, 1900, the Phono-Cinema-Theatre offered one minute talking or singing movies of eminent theatrical stars.

Mama don't take my chronophone awwwwayyyy!

Fellow Frenchman, Leon Gaumont, hosted a device called the Chronophone, which he succeeded in synchronizing projector and phonograph, by having the projectionist tweak the film speed incessantly. Gaumont developed this apparatus in competition with other commercial duplicators, and would enjoy a considerable amount of success in the course of the decade for his invention. In America, such systems would be exploited by the Actophone Company Camerafilm, and Edison's Cinemaphonograph. In Germany, Oscar Messter, in Sweden, Paulsen and Magnusson and in Japan the Yoshizawa Company all respectively developed sound film devices. in Britain, Hepworth's Vivaphone Pictures had a plethora of competitors with names like Cinematophone, Filmophone and Replicaphone.

But supposing that, in lieu of trying to match a separate disc recording to the film, the sound and image could be reproduced on the very same strip of film? The idea was explored: attempts were then made to utilize a needle groove cut along the edge of the film, but such ingenious efforts to marry phonography style recording to film projection was impractical. Alternative experiments, however had shown that sound waves could be converted into electrical impulses and registered on the celluloid itself; the sound track (a narrow band running down the edge of the film) was printed on to the film. As the film projected, the process would then be reversed. On the track itself would be variations of light, and this would translate into sound once again.

Not long after the the end of the Second World War, the development of radio inspired many engineers to work on methods of sound projection. As sound film systems would be patented, it was the monopoly of electrical and radio companies who usurped the patents and transcended to the new and exciting sound-film market. Throughout the early 1920s, the General Electric Company's focal point was a sound-on-film system and in the interim, Western Electric and Bell Telephone still favored a sophisticated method of synchronized disc reproduction.

Making some of De Forest Fires here.

Lee De Forest (1873-1961) was working individually on a sound-on-film system in 1923, a pet project that he was involved with for four years and he was now ready for his big debut with his revolutionary Phonofilms. His first public exhibition of short films was presented in the Rivoli theater in New York in April of '23, and it would be love at first sight and sound, and he was invited to go on tour with 30 theaters that were customized and wired to play it. The repertory contained not only tunes and turns by the contemporary Vaudeville artists, but also newsreel-style interviews with President Coolidge and various other people of the political world. Of note, was a melodramatic short - Love's Old Sweet Song - and musical accompaniments for James Cruze's ambitious The Covered Wagon (1923) and Fritz Lang's Siegfried (1924).

Phonofilms would garner some slight success, albeit was not considered anything momentous at the time. When De Forest showcased his systems to the honchos of the American cinema, they would not invest the vaguest interest. It would be perhaps the recession that clenched the film industry in the mid-Twenties, that would affect their better judgment. Public interest was waning; seat costs were rising, product quality was slipping, and audiences were becoming more demanding and discerning. Another serious threat was radio's fast growing popularity - a big broadcast was all it seemed to take to empty cinemas for an entire evening ( a similar feat is accomplished by today's television). Sadly, if the Hollywood tycoons would have taken De Forest's Phonofilms with more than a mere grain of salt, the cinemas could well have swayed their huge audiences back. As it was they went for stop-gap solutions, Vaudeville integration, potted light operas in between films, Saturday night lotteries - in other words - novelty at any price.

The other polarity was that the big companies were shrewd enough to foresee the threat that talking pictures presented to their vested interests, should they permanently gel with audiences. And the companies were proved absolutely right; when the talkies did come to fruition, the major studios and their equipment would become obsolete almost instantaneously, along with backlogs and silent films and bevies of former stars whose talents were more complemented to mime than to vocalization.

Warner Brothers decided to take the proverbial risk with the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. In later years, there was a common belief that - with nothing to lose by taking this plunge - they had grasped at Vitaphone in a last ditch effort to stave off ultimate bankruptcy.However, Professor J Douglas Gomery and others have proved that at this time, Warner Brothers were in pursuit of a policy of dramatic expansion .

Jack Warner and Al Jolson, madhatters

In 1924 the company had sufficiently impressed Waddill Catchings, a Wall Street banker of Goldman Sachs, to secure substantial investment, Catchings was apparently struck by Warner Brothers rigid cost accounting system; and with Harry Warner's blessing, he comprised a master-plan for long haul growth, not unlike an earlier plan whereby he helped to transform Woolworth's from a small local company to a national corporation, In 1925, Catchings would consent to Warner's offer of a seat on the board of its directors, and dedicated his energies to securing more capital.

Now finances, Warners would embark on a program of major prestige pictures, set about the acquisition of cinemas and distribution facilities, updated their labs, and developed their public image and exploitation methods. While at the same time, they started a radio station. The ramification of such colossal capital outlay, was that Warner Brothers went deeply, albeit calculatedly into the red in 1926. The 'near bankruptcy' conjecture is based on a misreading of fiscal accounts which showed, but never quantified and abrupt fall from a $1,102,000 profit to a $1,338,000 loss between March of 1923 and the end of the next year.

It was undoubtedly this expansionist mood that would make the Warners vulnerable to Western Electric, who since 1924 had persistently failed to interest the major producers in their sound-on-disc system of synchronization. In the later years, having survived all of his brothers, the youngest Warner, Jack was now inclined to claim credit for introducing sound pictures. In fact, it is believed that Sam Warner was the one responsible for having contact with sound through dealing with the affairs of the company's recently acquired radio station.

In June of 1925, the Warners would devise a new sound stage at the old Vitagraph studio in Brooklyn, New York and began to produce a a series of synchronized vignette shorts. On April 20, 1926, the company established the Vitaphone Corporation to lease Western Electrics sound system and would also now have the legal right to sub-licence. Sam Warner embarked on the pan to launch this program for Vitaphone; his expenditure of an exorbitant $3 million on it, negates any theory that this was a bankrupt studio we are talking about

This culmination of this exasperating activity would come on August 6, 1926, with the memorable Vitagraph premiere of Don Juan - the first film with a completely synchronized score. ( It's imperative to recognize here that it was a musical accompaniment, and not talking pictures that appealed to the film moguls). The now supporting format consisted of a series of refined musical shorts, preceded by a stodgy filmed speech of introduction by Will Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers' Association.

The first Vitaphone program was testament to Warners' faith and monetary investment - it ran in New York for more than six months - and henceforth, the brothers were passionately committed to sound. The proud Warners would now make the announcement - that all upcoming releases would be provided with Vitaphone accompaniments, and the process of equipping major cinema chains with sound throughout the country would begin. In October of 1926 Warners would presetting a second Vitaphone program and this time with Sydney Chaplin in The Better 'Ole, and some new short productions of vaudeville material in contrast to the prestige shorts shown ad the Vitaphone premiere only two months prior.

Although most of the major companies were all peepers and waiting, behind the scenes, William Fox's film company would purchase the rights in a sound system so close to De Forest's Phonofilm, that it would become the subject of extensive litigation. Fox integrated in his system, elements from both Phonofilm and the German Tri-Ergon system ( Fox also owned the American rights of this), and would launch Fox Movietone with a rota of shorts on January 21, 1927. By May, he presented a synchronized version of Frank Borzage's Seventh Heaven. The supporting program would include a dialogue short - Chic Sale's sketch They're Coming To Get Me. In June, a brand spanking new Movietone program included sound film of Lindbergh, Coolidge and Mussolini respectively, and in October 1927 Fox would introduce a regular segmented Movietone newsreel.

If there were any reservations that the future of the film industry was bound up with sound - would be debunked by the onset of success with The Jazz Singer, which had it's premiere in October 6, 1927. The public had already witnessed films that contained song and speech. What seems to have sparked and fueled their curiosities, in this maudlin melodrama about a cantor's son who rebelliously becomes a jazz musician, was the down to earth dialogue scenes ( Al Jolson improvised them all) and that he would address these words in the fourth wall style.

It was official, sound films could not be dismissed anymore, and the major corporations had no plans to ignore them. After the premiere of Don Juan, Adolph Zukor's Famous Players Company would begin talks and negotiations with Warners and Vitaphone, but unfortunately these had broken down. In December of the year 1926, Zukor accumulated a committee that would represent most of the major companies - Famous Players Loew's Producers Distributing Corporation, First National, United Artists and Universal - who concurred upon mutual research and united action to the matter of sound pictures.

And for the next year, the committee would receive reports from technical experts on the array of systems that were now available to them; Vitaphone was now able to be subleased from Warners; Fox's Movietone would also pique their interest. Photophone, developed at General Electric; was on loan from RCA, and Western Electric, although plugging their disc apparatus, were now on the case of developing their own sound-on-film systems. The choice was still balanced and justified between sound-on-film disc and sound-on-film. The aim was to settle upon a system that offered compatibility among all the various equipment. And this would be to divert any kind of wrangling and litigation procedures over patents that had beset the early days of cinema.

The other studios analysed tests and deliberated. Warners and Fox, gained a tacit, but considerable advantage. It would not be until May of 1928 that the six companies would reach and agreement with Western Electric to adopt their sound-on-film system, and a year following this, a multitude of the smaller Hollywood outlets, would follow suit and adhere to this agreement. Warner Brother's extensive investment in sound-on-disc production would be accordingly from 1927 to 1929, the was clearly some writing on the wall, for the Vitaphone system less than a year after The Jazz Singer's premiere. Warners would soon follow the other studios and themselves adopt sound-on-film whilst still retaining the name Vitaphone.

The year of transcendence would be 1928, the cross-over would not occur over night. To re-equip each studio was a lengthy process and for many months, the sound films would continue to see their releases in alternative silent versions, consequently, sound effects and music were toggled on to silent films to extend their commercial existences. Nonetheless, the silent cinema, even considering it's refinement and artistic foundation, had perfected over the last three decades and had instantly become antiquated and archaic. There would be some 80 features of sound that would be made in the course of 1928.

Part One of my Sound & Vision series - next chapter ' The Transition of Sound to Talkies' coming soon from The Filmographer.

-screenshot.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment